Return of the King

By Nicole Berner, The Scene

December 18, 2003

|

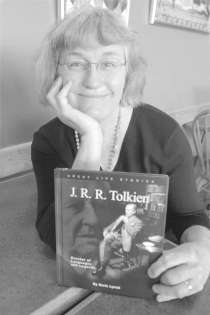

| Bloomington author Doris Lynch has written a new biography of J.R.R. Tolkien for young readers, J.R.R. Tolkien: Creator of Languages and Legends. Staff photo by David Snodgress. |

When people think of J.R.R. Tolkien, hobbits and wizards generally come to mind.

But when Bloomington writer Doris Lynch talks about the elusive author, she paints a picture of a devout Catholic with a love for trees and a distaste for fame.

"He wouldn't have liked the celebrity stuff at all," Lynch said of the author of The Lord of the Rings trilogy, who died in 1973.

Tolkien had an eccentric side, bicycling to work in his trademark black cape, for example, but for the most part, he was a man simply in love with words.

Lynch, a creative writing teacher at Ivy Tech State College and reference librarian at the Monroe County Public Library, recently completed a biography of the author geared toward young readers, J.R.R. Tolkien: Creator of Languages and Legends.

Like most people, Lynch had heard of the author, but she knew little about him before her research —just that he was an Oxford University professor with an interest in language.

"His family keeps really tight control," Lynch said, adding that Tolkien's grandson sold the rights to the blockbuster movies, and "most of the rest of the family was angry about it."

By contacting Tolkien's childhood school in England, traveling to see original manuscripts and letters and reading biographies, what Lynch ultimately learned about Tolkien leaves her no doubt that the hoopla surrounding The Return of the King — the final movie installment of the trilogy, which opened Wednesday at Showplace 12, west — would be a thorn in his side, she said.

He disliked anyone changing anything about his texts — including typeface and illustrations, Lynch said.

Starting with his first taste of celebrity in the '60s, Tolkien also had been awakened in the middle of the night more than once by fans across the Atlantic Ocean who were ignorant of — or paid no attention to — the time difference between England and the United States.

He called the stateside fascination with him a "deplorable cultus," and he launched lawsuits to fight the U.S.-based pirating of hundreds of thousands of copies of his work, Lynch said.

BECOMING J.R.R.

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien was born in South Africa but raised in England from the age of 3, when his father died of rheumatic fever.

He grew up with his mother and brother in the countryside outside Birmingham, in an idyllic setting not unlike the landscape in the land of the hobbits, Lynch said.

While he wasn't very political, living in the countryside fostered a deep caring about trees, she said: "He was an environmentalist. He really loved trees Ö He felt really strongly when the suburbs were taking over."

His mother moved her sons to the city of Birmingham so they could attend school, and in an early grade, Tolkien learned Latin and French. It sparked a passion for languages — including a fondness for making them up — that led Tolkien to learn about 15 languages by the time he reached his teens.

"He would buy books and study them on his own," Lynch said.

Tolkien's mother died of diabetes when he was 12, and all his life, he placed much importance on family. He later had four children of his own.

A stint in the army in World War I was a pivotal experience for him, Lynch said.

"He saw all that brutality Ö I think a lot of the violence in his movies comes from that," Lynch said.

Tolkien escaped death — his whole regiment eventually died in the war — because he contracted "trench fever" and was sent home. The hospital he recovered in is where he first thought of Middle Earth, and subsequent bouts of the fever gave him much time recovering at home, where he thought and wrote.

"He wanted to create a mythology for England," Lynch said.

Tolkien had begun writing in college, mostly academic works on linguistics. By the time he created Middle Earth, he was so well-versed in mythologies that he had read in their original languages, that his words have context beyond their surface meanings.

BEYOND BOOKS

An underlying theme in Tolkien's work is good versus evil, which is reflective of his strong Catholic faith.

Indiana University professor of folklore and ethnomusicology Gregory Schrempp admits that fantasy literature is not his specialty, but he thinks the Catholic influence on Tolkien's work is strong — "first in the love of the idea of an overarching complexity and systematicity of the cosmic and social order (and disorder) Tolkien is known for."

He added that he perceives "a minor tradition of Catholic writers who create and use mythology-like fantasies to present what are often, underneath, rather conventional religious moral messages."

That group includes C.S. Lewis, whom Lynch says was changed from an agnostic to a Christian through his friendship with Tolkien.

"They would meet in C.S. Lewis' rooms (at Oxford University) on Thursday nights. They would bring writings and critique each other," Lynch said. The two remained close friends for about 25 years.

Because of Tolkien's known ties to Catholicism, Marquette University in Milwaukee purchased some of his original texts a long time ago, and Lynch traveled to the Catholic school to see them.

"It bought most of the manuscripts for under $6,000," Lynch said.

Another Christian college, Wheaton College in Wheaton, Ill., owns personal correspondence between Tolkien and Lewis.

Lynch's book is available through Scholastic Inc. and includes photographs, a Tolkien timeline, information about English life during Tolkien's time and numerous Web sites of interest to his fans.

Reporter Nicole Berner can be reached at 331-4357 or by e-mail at nberner@heraldt.com.

|

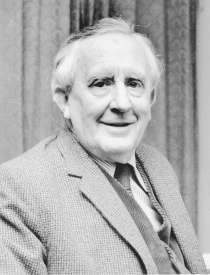

J.R.R. Tolkien, 1967. AP Photo. |

|